|

Share this page!

|

TIMBERFISH

|

Tweet this page!

|

Watch & share our TV Segment!

TimberFish’s solution is a new

ecotechnology that is environmentally

sound and economically competitive

in today’s marketplace.

|

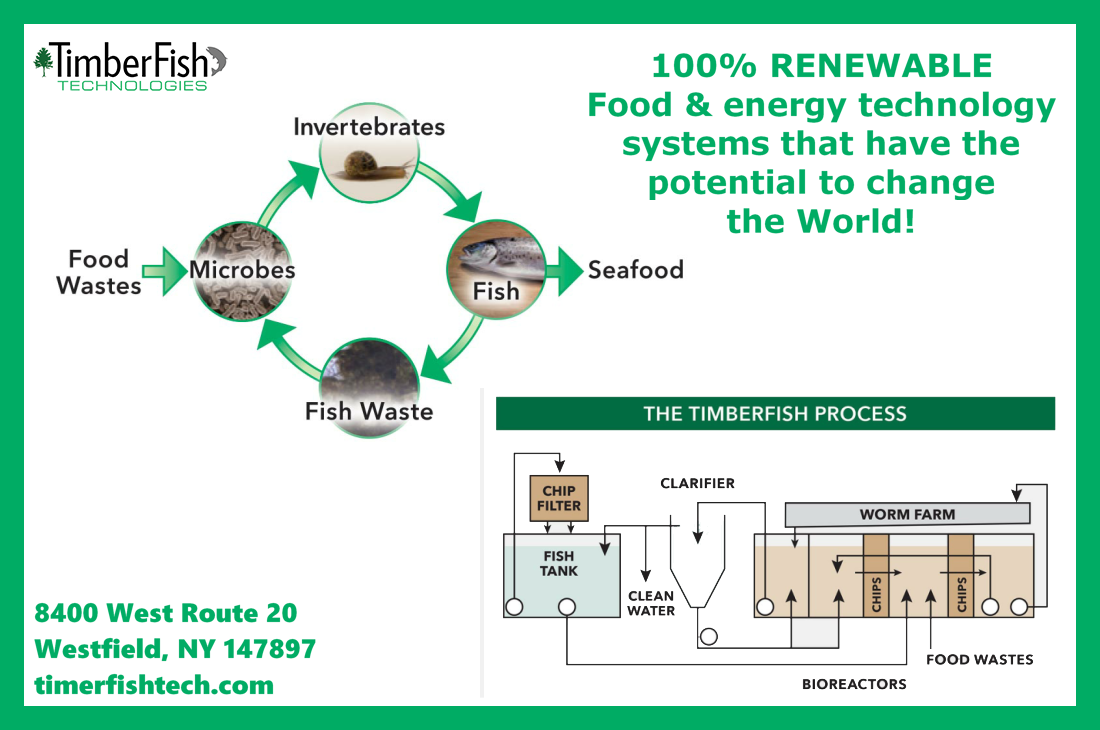

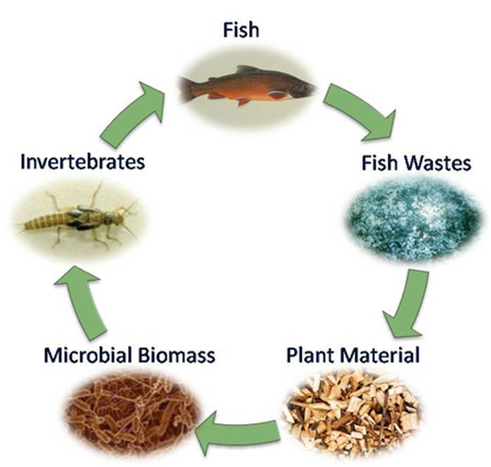

TimberFish Technologies uses food production waste streams to grow delicious, clean and safe seafood while discharging clean water. TimberFish Technology Bioconverts Clean Organic Waste Streams Into Salable Seafood. Food and Beverage Producers who have clean but high strength waste streams often find that these streams are costly to dispose of under current environmental regulations. The solution that TimberFish offers is a system that combines these wastes with nutrients and unutilized plant materials, to create a new food chain that produces marketable seafood. Selling this seafood reduces or eliminates the costs associated with the treatment and disposal of the wastes.

|

Rising Populations and Environmental Pollution Threaten Our Future’s Food Supply and Safety.

Our existing food supply is based on the production of fruits and grains from farmed land, and seafood harvested from our oceans. Most land suitable for farming is already in production and our oceans are over-fished. Human populations are rising and there are growing concerns about climate change and environmental pollution – all of this is putting increased pressure on food production. |

TimberFish Origins and History

The Microbial Tank Farm prototype

(1973)

Here I am working with the Relational Systems group at the Center for Theoretical Biology at the State University of New York at Buffalo. However, I am living in the country so in my spare time I am fermenting weeds in barrels, converting them into a microbial biomass, and feeding them to fish, well, minnows actually (this is the first prototype that would eventually become TimberFish).

The microbial biomass

Feeding the biomass to minnows.

This led to a first round of entrepreneurial startups focused on environmental issues. But this was the 1970s and outside of wastewater treatment there was not a lot of interest so I went to work in a municipal wastewater treatment plant.

Town of Amherst, NY Advanced

Wastewater Treatment Plant

(1979 - 1989)

This was a 36 MGD state of the art advanced wastewater treatment plant where I was both chemist and process superintendent for ten years. The plant was a two stage pure oxygen activated sludge system with biological nitrification and phosphorus removal systems, anaerobic digestion, multiple hearth incineration, and rapid sand filtration for effluent polishing. We made our own oxygen and sodium hypochlorite for disinfection.

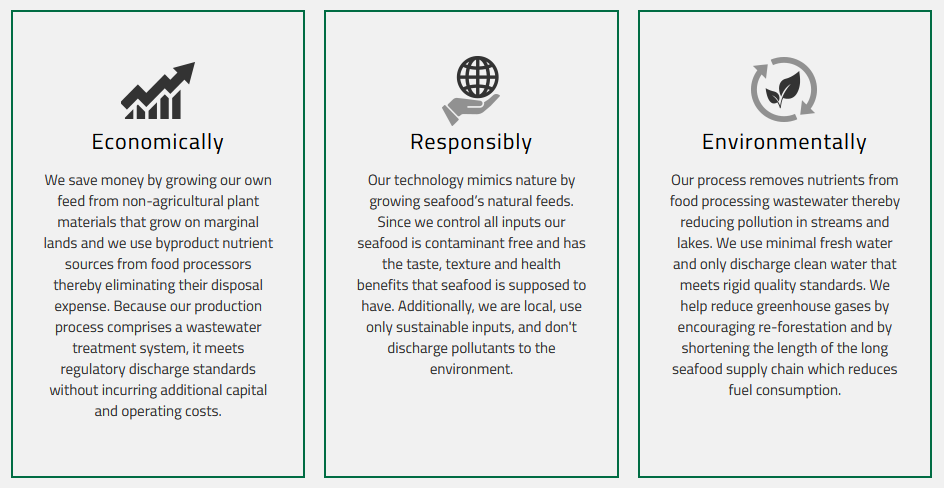

I developed a bio-monitoring system where we grew trout, fathead minnows, daphnia and gammarus in our effluent prior to disinfection. We grew the trout in a pond fed with plant effluent and harvested them.

Since I ran the lab as well, I analyzed the trout and ate them.

The activated sludge and biological nutrient removal technologies that were incorporated in municipal wastewater treatment plants proved to be very successful at dealing with point sources of water pollution. However, environmental pollution problems continued to grow and the focus shifted to non source pollution mainly associated with agriculture.

The municipal experience had enhanced the understanding of how large complex systems of microorganisms work ecologically, and this again presented an entrepreneurial opportunity.

Bion Environmental Technologies

(1989 to 2008)

I developed and patented the initial technology and was president for the first ten years, director and chief technology officer after that. We build over 30 manure and nutrient management systems for large animal agriculture and fruit processing facilities.

This is a large dairy farm in Florida.

This is a smaller dairy farm in New York.

These systems utilized a low oxygen nitrification - denitrification technology I developed as well as constructed wetlands for effluent polishing.

This is a large hog farm in North Carolina. The purple color is from

anaerobic photosynthetic purple sulfur bacteria.

anaerobic photosynthetic purple sulfur bacteria.

This is a treatment system for a large citrus processing plant in Florida.

TimberFish

(2008 to present)

The Bion systems primarily dealt with wastewater treatment and the production of a beneficial soil product. The market for the systems was regulatory driven and did not provide an economic benefit for the farmers and fruit processors. So I started again and this time focused on integrating fish production as the key element for a successful commercial system.

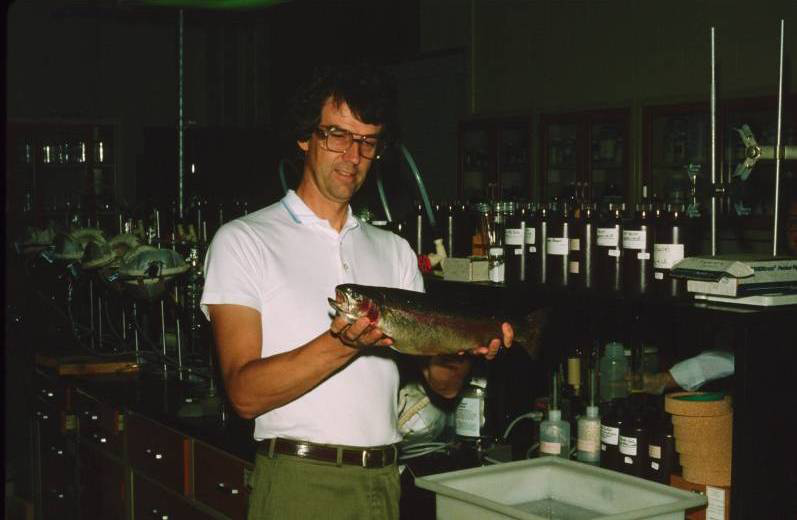

All good technical entrepreneurial startups are supposed to begin in your garage but in this case we started in the basement. Here is an initial bioreactor for the production of a microbial biomass.

All good technical entrepreneurial startups are supposed to begin in your garage but in this case we started in the basement. Here is an initial bioreactor for the production of a microbial biomass.

The microbial biomass was then transferred to worm farm prototypes and fish tanks

And then it was suggested that the whole system should be moved into the garage.

From the garage we moved into the woods.

This is one of the first proof of concept systems in Westfield, NY.

These two pictures show rainbow trout that were initially stocked and then grown to marketable size in this system for one year.

The system ran all winter. Here I check it out in January.

Again we harvested fish, and ate them.

The success of the proof of concept trials in the woods in Westfield led to an independent third party field trial at the Freshwater Institute in Shepherdstown West Virginia. The Freshwater Institute is a program of The Conservation Fund and is one of the premier research institutes in the world on recirculating aquaculture systems.

Here is the experimental prototype they constructed and operated to evaluate the TimberFish Technology.

And here are trout grown in this system.

All of this experience has recently culminated in the TimberFish facility at the Five & 20 Spirits & Brewing location in Westfield, New York.

This system began producing biomass in September 2016

It continued to grow biomass and degrade stillage during the winter of 2016 – 2017.

It began growing fish in September, 2017, and resides inside today.

RAW VIDEO POOL

All videos have been synced, partially color graded and vetted from larger video pools that were sot for the project. These will all be color graded, edited and effected to a much further degree on the final edits. The sound has been partially fixed and processed where possible and will be finalized on the respective, final edits. These are still in very preliminary form, but are ready for review for the start of the final edit process. They will stay on this page for future reference as we progress into the creation and collaborative part of the video portion of this project.

"5&2O" INTRO SPOTS

|

5&20/"DWNY" - Initial Introduction #1:

|

5&20/"DWNY" - Initial Introduction #2:

|

"DWNY" TV SHOW INTERVIEWS

|

"DWNY" TV Show interview #1

|

"DWNY TV" Show interview #2

|

FACILITY SHUTDOWN

|

Shutdown (Lab Conversation)

|

Shutdown (Site Explanation)

|

|

Shutdown (On--site #1)

|

Shutdown (On--site #2)

|

|

Shutdown (On--site #3)

|

Shutdown (On--site #4)

|

|

Shutdown (On--site #5)

|

Shutdown (On--site #6)

|

|

Shutdown (On--site #7)

|

Shutdown (On--site #8)

|

Shutdown (On--site #9)

FACILITY SHUTDOWN/DINNER AT "BRAZILL'S"

Brazill's Dinner #1

|

Brazill's Dinner #2

|

Brazill's Dinner #3

|

|

|

|

Impacts and Consequences

of the Core Curriculum

Reflections for the 50th Reunion

of the Class of 1964

Jere Northrop

I came to Amherst College planning be a scientist and found that I loved Science 1-2 and the Chem–Bio sequence. But I loved English 1-2 even more. It was my favorite course. Ask a question relevant to your own experience, something that you did. What does it mean, what do you know about this, how do you know it. No one knows the answers they said. But of course I knew that the scientists really did.

When I hit the biology part it occurred to me that they, the biologists, didn’t actually know the answers. Biology was not a science, at least not in the sense that physics was. So I became a biologist, what a great opportunity. I did grad school, post doc, all the while still asking the questions, what does it mean, what do I know. What do they know. And it began to look like maybe none of them, not even the physicists, really knew all the answers.

I remembered Professor Gordon of the physics department, in an informal panel discussion with the freshman class, explaining that physics was just a model. Constructed from carefully stated hypotheses, experimental tests and observations. It is a model that may or may not be useful. You had to work with it to see what it could do, what you could do with it. But the physics model, often called reductionism and viewed as a belief that physics will eventually explain all of biology, all of life, even ourselves, was generally accepted by society.

From the perspective of English 1-2 the reductionist model, did not contain the words that could talk to me about the conscious, linguistic, and emotional experiences that constituted my life. My personal experiences did not fit in the model. Despite the fact that physics was enormously successful in many areas, I began to wonder if any of biology really fit in the model.

So at the end of 1969 I dropped out, started writing, started looking for a new paradigm, something, some model that would include me as well. English 1-2 included my experience, meaning, and knowing, but it did not do anything. Science 1-2 had lots of doing, lots of capability and success, but I and my emotional and linguistic nature were not part of the model. How could these two seemingly separate world views be integrated. What could I do to bring these together.

In 1971 I joined Jon Ray Hamann and his Relational Systems Working Group at the Center for Theoretical Biology at SUNY Buffalo. Part of what that group did was to participate in College E, one of the experimental colleges that was started to provide new educational alternatives in the SUNY system. College E was set up as a cooperative consensus decision making organization in which students and teachers interactively created and taught courses that were defined relative to student interests. It was almost a complete opposite of the Amherst College Core Curriculum.

The operation of College E was heavily influenced by the decision model of Relational Systems Theory and its use of the Maximum Entropy Principle. The focus was on foundational presumptions and how these related to decisions and cooperative action. The integration of this perspective with that of English 1-2 was beginning to form the basis of how to move beyond reductionism.

During this time I continued to work with experimental biology since I had become very fond of “doing” it in graduate school. DNA looked sort of like language, so did the songs of birds. Could all this fit together in highly interconnected ecosystems that integrated me, English 1-2, and experimental science? Was this the new model?

When I hit the biology part it occurred to me that they, the biologists, didn’t actually know the answers. Biology was not a science, at least not in the sense that physics was. So I became a biologist, what a great opportunity. I did grad school, post doc, all the while still asking the questions, what does it mean, what do I know. What do they know. And it began to look like maybe none of them, not even the physicists, really knew all the answers.

I remembered Professor Gordon of the physics department, in an informal panel discussion with the freshman class, explaining that physics was just a model. Constructed from carefully stated hypotheses, experimental tests and observations. It is a model that may or may not be useful. You had to work with it to see what it could do, what you could do with it. But the physics model, often called reductionism and viewed as a belief that physics will eventually explain all of biology, all of life, even ourselves, was generally accepted by society.

From the perspective of English 1-2 the reductionist model, did not contain the words that could talk to me about the conscious, linguistic, and emotional experiences that constituted my life. My personal experiences did not fit in the model. Despite the fact that physics was enormously successful in many areas, I began to wonder if any of biology really fit in the model.

So at the end of 1969 I dropped out, started writing, started looking for a new paradigm, something, some model that would include me as well. English 1-2 included my experience, meaning, and knowing, but it did not do anything. Science 1-2 had lots of doing, lots of capability and success, but I and my emotional and linguistic nature were not part of the model. How could these two seemingly separate world views be integrated. What could I do to bring these together.

In 1971 I joined Jon Ray Hamann and his Relational Systems Working Group at the Center for Theoretical Biology at SUNY Buffalo. Part of what that group did was to participate in College E, one of the experimental colleges that was started to provide new educational alternatives in the SUNY system. College E was set up as a cooperative consensus decision making organization in which students and teachers interactively created and taught courses that were defined relative to student interests. It was almost a complete opposite of the Amherst College Core Curriculum.

The operation of College E was heavily influenced by the decision model of Relational Systems Theory and its use of the Maximum Entropy Principle. The focus was on foundational presumptions and how these related to decisions and cooperative action. The integration of this perspective with that of English 1-2 was beginning to form the basis of how to move beyond reductionism.

During this time I continued to work with experimental biology since I had become very fond of “doing” it in graduate school. DNA looked sort of like language, so did the songs of birds. Could all this fit together in highly interconnected ecosystems that integrated me, English 1-2, and experimental science? Was this the new model?

Here was my lab in 1973. That’s me in the middle.

Eventually I had to get a job, in the real world what you do probably should relate to what you think and what you know. So after much searching for a next step I started working at a large advanced biological wastewater treatment plant. By now I was thinking that consciousness and language had to be the primaries of the model and so this looked like a job that had some interesting possibilities. The large microbial biomass, and the human staff that observed, analyzed, and directed (talked to?) it, had to function to achieve an objective.

Here was my lab in 1981. I’m down there in one of the buildings.

By 1986 I was raising fish in wastewater effluent

After ten years I moved into manure management for large animal agriculture. My brother (Amherst 1965) and I, two core curriculum survivors, formed Bion Technologies. By now English 1-2 had evolved into a program for creating languages. The languages had to subsume mathematics and science, thereby integrating English 1-2 and Science 1-2. In parallel with this the “lab” that might validate this new model turned into a business. The applications in environmental biotechnology had to be integrated into even more real world tests than before.

Here is a hog farm in 1998. That Amherst purple color is from anaerobic photosynthetic

purple sulfur bacteria in the manure management system.

purple sulfur bacteria in the manure management system.

I began to conceptualize these systems as semiotic pragmatic bio-computers. The microbes were not only alive, they were conscious, they could communicate with each other, have memories and emotions, good days and bad days. Looking at them from an information theory perspective I could see that the microbial genomes were statements, hypotheses, what the microbes “knew”. They replicated rapidly, mutated often, continually testing their evolving and ever changing hypotheses with or against a complex environment. Process control became a dialogue.

Bion Technologies still exists (www.biontech.com), and it still has a chance to do great things for our environment, but overall it has been a disappointment. New management came in in 1999 and business and financial realities forced the vision and application to narrow. An increased reliance on standard engineering brought with it a greater use of the reductionist paradigm. No one wanted to hear about semiotic pragmatic bio-computers any more. So during the period from 2002 through 2008 I transitioned out of Bion altogether.

The dream did not die however. By 2002 the language creation direction had evolved into an approach to a Universal Language and coalesced into a stable format that derived from consciousness, relation, and language. So I put it up on the internet. See www.ododu.com It is very much a work in progress, but the non reductionist cosmology that it represents has been instrumental in guiding a new series of applications. These initially focused on several “Advanced Ecological English 1-2 labs”, which in turn led to the incorporation of another company that I cofounded in 2008, TimberFish Technologies, (see www.timberfishtech.com)

Bion Technologies still exists (www.biontech.com), and it still has a chance to do great things for our environment, but overall it has been a disappointment. New management came in in 1999 and business and financial realities forced the vision and application to narrow. An increased reliance on standard engineering brought with it a greater use of the reductionist paradigm. No one wanted to hear about semiotic pragmatic bio-computers any more. So during the period from 2002 through 2008 I transitioned out of Bion altogether.

The dream did not die however. By 2002 the language creation direction had evolved into an approach to a Universal Language and coalesced into a stable format that derived from consciousness, relation, and language. So I put it up on the internet. See www.ododu.com It is very much a work in progress, but the non reductionist cosmology that it represents has been instrumental in guiding a new series of applications. These initially focused on several “Advanced Ecological English 1-2 labs”, which in turn led to the incorporation of another company that I cofounded in 2008, TimberFish Technologies, (see www.timberfishtech.com)

This is one of the initial TimberFish Proof of Concept Systems in Westfield, NY 2009

TimberFish Field Trial at the Freshwater Institute in Shepherdstown, WV, 2010

The TimberFish Technology uses non-contaminated plant material and nutrients as food for microbes, which are then eaten by invertebrates which are in turn eaten by fish in a closed re-circulating aquaculture system. Waste products from one level are foods for other levels. If the Bion systems can be viewed as bio-computers, the TimberFish systems look like ecological minds. Multiple levels of conscious communicating organisms interacting in a synergistic and selfsustaining ecosystem.

The power of this integrated multitrophic ecosystem approach, which I see as being a technology that incorporates the power of English 1-2, “knits knowing and communicating into its very being” if you will, has guided TimberFish to the point where it could start to provide real world, large scale and economically viable resolutions to many of our most urgent problems. These are problems that the reductionist paradigm has created and doesn’t seem to be able to resolve, at least not in an economic and ecologically sound manner. It isn’t getting done. In contrast, a TimberFish technology system projects to integrate all of the following features in a profitable business operating in today’s marketplace;

Sustainable local contaminant-free food production

Renewable energy

Water purification and preservation

Economic incentives for reforestation and deforestation avoidance

Climate change reversal

Enhanced biodiversity and ecosystem stability

We expect that by June of 2014, our first commercial prototype, the TimberFish Wine-Fish Project at the Mazza distilleries operation in Westfield, NY, will have been constructed, and that it will become operational during the summer. This application should produce 25,000 pounds per year of high quality fish such as Speckled Trout, Artic Char, or Atlantic Salmon. From there it’s on to 2+ million pounds per year facilities next to all significant population centers.

I realize that to challenge any well established societal paradigm, particularly one as strong and established as the reductionist paradigm is today, is to risk being viewed as a crank, crackpot or heretic. Yet the company of that group is not all bad. I still remember Theodore Baird, writing about the “experience of understanding just what it was like to have lived in the past” saying “Yet in looking back it is plain how dreadfully wrong nearly everyone was about nearly everything” page 4 of “The Most of It” Theodore Baird, Amherst College Press, 1999.

So lets listen to that other great voice that permeated English 1-2, Robert Frost

“I’m going out to clean the pasture spring;

I’ll only stop to rake the leaves away

(And wait to watch the water clear, I may):

I sha’n’t be gone long.- You come too.”

Robert Frost, “The Pasture” North of Boston 1915.

The repeated references to English 1-2 may be difficult to understand for those who did not actually take the course at Amherst College during the years 1938 – 1966. An excellent description of this course is available in “Fencing with Words, A History of Writing Instruction at Amherst College during the Era of Theodore Baird, 1938-1966” by Robin Varnum, National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Illinois, 1996.

November 15, 2013

Sustainable local contaminant-free food production

Renewable energy

Water purification and preservation

Economic incentives for reforestation and deforestation avoidance

Climate change reversal

Enhanced biodiversity and ecosystem stability

We expect that by June of 2014, our first commercial prototype, the TimberFish Wine-Fish Project at the Mazza distilleries operation in Westfield, NY, will have been constructed, and that it will become operational during the summer. This application should produce 25,000 pounds per year of high quality fish such as Speckled Trout, Artic Char, or Atlantic Salmon. From there it’s on to 2+ million pounds per year facilities next to all significant population centers.

I realize that to challenge any well established societal paradigm, particularly one as strong and established as the reductionist paradigm is today, is to risk being viewed as a crank, crackpot or heretic. Yet the company of that group is not all bad. I still remember Theodore Baird, writing about the “experience of understanding just what it was like to have lived in the past” saying “Yet in looking back it is plain how dreadfully wrong nearly everyone was about nearly everything” page 4 of “The Most of It” Theodore Baird, Amherst College Press, 1999.

So lets listen to that other great voice that permeated English 1-2, Robert Frost

“I’m going out to clean the pasture spring;

I’ll only stop to rake the leaves away

(And wait to watch the water clear, I may):

I sha’n’t be gone long.- You come too.”

Robert Frost, “The Pasture” North of Boston 1915.

The repeated references to English 1-2 may be difficult to understand for those who did not actually take the course at Amherst College during the years 1938 – 1966. An excellent description of this course is available in “Fencing with Words, A History of Writing Instruction at Amherst College during the Era of Theodore Baird, 1938-1966” by Robin Varnum, National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Illinois, 1996.

November 15, 2013